The Black Brigade of Cincinnati

The Black Brigade of Cincinnati was a military unit of African American soldiers that was organized in 1862 during the American Civil War, when the city of Cincinnati, Ohio, was in danger of being attacked by the Confederate Army.

As the City of Cincinnati mobilized to meet the forthcoming threat of Confederate invasion in late summer 1862, all able-bodied men were expected to help defend the city.

African American men were no exception. They organized themselves into a unit to take up arms against the Confederates. Fearing armed African Americans, however, city officials rejected their offer, going so far as to block a planned second meeting by the group. Authorities told the Black men that it was not their war and forbade further meetings.

Undeterred, these patriotic African American men endeavored to contribute to the defense of Cincinnati and, in the process, became the first organized African American group employed for military purposes in the Civil War. Unfortunately, the beginning actions of what would become known as the “Black Brigade” would be coerced and founded in bigotry.

On September 1, General Lew Wallace, the man responsible for the city’s defense, intended to enroll Blacks to construct defensive fortifications in northern Kentucky. Police abruptly and forcefully rounded up Black male residents to build fortifications. This often happened at gunpoint and with rough treatment, with no plan or explanation given. Police gathered the men into a confined mule pen on Plum Street, leaving them uncertain of their fate. Fearing abandonment in Kentucky and enslavement, the men trembled with anxiety.

Police forcibly brought roughly 400 men to regimental camps. They were subjected to grueling conditions for two days, working non-stop for 36 hours without rest and receiving only meager rations. This sparked outrage, with the Cincinnati Daily Gazette demanding fair treatment for the men, urging them to “treat our colored fellow soldiers civilly” and “like men.”

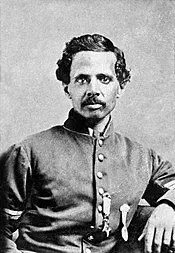

All of this changed when General Lew Wallace saw the treatment given to the group. On September 4, General Wallace appointed Judge William Martin Dickson to lead the African American men. He went into the military camps and rescued those who were forced into labor. Once all the men were accounted for, Dickson sent them home to their families. He asked them to consider returning voluntarily the following day.

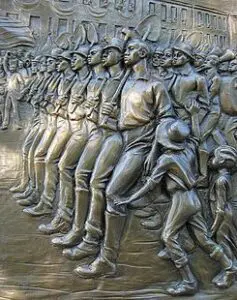

Dickson organized the men along military lines and christened them the Black Brigade. The unit marched across the river under the National flag, digging rifle pits, clearing trees, and building forts, magazines, and roads.

Related Article: The History of African Americans in Cincinnati

On September 5, 700 Black men voluntarily reported for duty, including many who were securely hiding from the police. Later, the Black Brigade soldiers received their military unit flag and $13 a month—a Union Army private’s pay.

A total of 1000 men served the Black Brigade. In its numbers, 700 men built forts, magazines, and miles of military roads and breastworks along the riverfront, and 300 men worked in military camps and on the gunboats.

On September 17, as a token of appreciation for their treatment and his defense of their rights, they gave Judge Dickson an engraved sword.

Fifteen days after forming, on September 20, the Black Brigade disbanded as the threat to Cincinnati waned. They tirelessly cleared hundreds of acres of forest and dug miles of rifle pits, fortifying the city’s defenses.

Though the brigade was disbanded, it would not end the war for some of them. Many would go on to serve honorably in the Union Army, some enlisting in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, made famous by the movie Glory.

The battle flag given to them by Dickson and Lupton is now in the collections of the Ohio Historical Society.

Related Article: Stories of the Underground Railroad and the Important Ties to Cincinnati

Many Black Brigade members later served in the Union Army, some in the famous 54th Massachusetts Regiment. The Black Brigade was believed to be the first utilization of African Americans for military purposes in the North.

In 2012, the US Senate passed a resolution recognizing members of the Cincinnati Black Brigade as veterans. The Black Brigade monument in Smale Riverfront Park pays tribute to this significant moment in Cincinnati’s social history.

Sources

Black Brigade of Cincinnati – Wikipedia

Cincinnati History Library and Archives – cincymuseum.org

About The First 28

The First 28, graciously sponsored by the Greater Cincinnati Foundation, celebrates Black Cincinnatians who were the first in their fields. Each day during Black History Month, we will celebrate athletes, artists, business leaders, civil rights activists, educators, physicians, and politicians.

Recognizing Steve Preston

This article’s information was provided in a presentation by Steve Preston.

Steve Preston is the Education Director and a Curator of History at Heritage Village Museum. He received his MA in Public History from Northern Kentucky University.

The Voice of Black Cincinnati is a media company designed to educate, recognize, and create opportunities for African Americans. Want to find local news, events, job postings, scholarships, and a database of local Black-owned businesses? Visit our homepage, explore other articles, subscribe to our newsletter, like our Facebook page, join our Facebook group, and text VOBC to 513-270-3880.

Images provided by Wikipedia

Comments are closed.