Many African Americans had generational ties to the West End. Then the most significant transformation of this region of the city occurred.

The West End neighborhood in Cincinnati, Ohio, was established soon after Israel Ludlow, Matthias Denman, and Robert Patterson purchased eight hundred acres of land from John Cleves Symmes and founded the Queen City in 1788.

The West End neighborhood in Cincinnati, Ohio, was established soon after Israel Ludlow, Matthias Denman, and Robert Patterson purchased eight hundred acres of land from John Cleves Symmes and founded the Queen City in 1788.

Although the town was founded in 1788, the name Cincinnati did not take hold until two years later, in 1790.

Receive our newsletter for all things Black Cincinnati!

By the mid-19th century, Cincinnati had become a significant machine tool manufacturer and led the nation in producing ale, beer, finished clothing items, meatpacking, soap, and whiskey.

Thousands of African Americans, many from slavery, migrated to the city to the Queen City. In 1826, Cincinnati had 690 African American residents. Whites, primarily Irish and German immigrants, were the dominant ethnic groups, but by 1860 the number of African Americans had grown to about 3,600.

Many of the new African American residents to the city settled on the outskirts of the central business and commercial districts. Most of these new arrivals migrated from the South in high numbers, based on the promise of stable jobs, especially in the steamboat industry, and the belief in improved race relations. More importantly, however, the city area most African Americans traveled to soon became known as the West End.

Related Article: Learn about the history of African Americans in Cincinnati

These city economic and population changes also led to a significant real estate boom in the West End. Beginning during the 1830s, there was a massive transformation of the entire region’s residential makeup and industrial patterns.

These city economic and population changes also led to a significant real estate boom in the West End. Beginning during the 1830s, there was a massive transformation of the entire region’s residential makeup and industrial patterns.

Along the Ohio River, an African American community known as Little Bucktown, or just Bucktown, had been established at the lower part of the West End. Right next to Bucktown, on its west and north sides, were several newly established Irish communities.

Related Article: The recurring history of racial tensions and economic divide in OTR

A little higher up, on Third Street, an upper-class and very influential white community, which pre-dated the 1830s, began to expand along Fourth and Fifth Streets.

Between Sixth and Laurel Streets, a newly established group of middle and lower-middle-class white Cincinnatians had started to push out a small but potent group of farmers who had settled in the West End during the early 1800s.

Also, this new group of white Cincinnatians was starting to displace older factories, cemeteries, and numerous other locally established businesses and institutions that had been in the region for decades.

The most significant transformation of this city region initially occurred in the upper West End. Slaughterhouses, breweries, and soap factories established in this area during the early 1820s intensified in their development between the 1830s and the 1870s.

Also, hundreds of tenement houses from workers began to appear throughout this part of the city. Gradually, the entire West End became one of the most densely populated areas in the city.

Related Article: Cincinnati’s ties to the Underground Railroad

Also notable was that very little racial violence initially occurred in the region and the city. However, this situation changed overnight with race riots in 1829, 1836, 1842, 1863, and 1884 respectively.

As a result, by the turn of the century, the wealthy class abandoned many affluent white residents in the lower and upper West End. This situation mainly occurred because several newly developed neighborhoods opened on the hillsides of Cincinnati.

Also, many industries began to move to these same regions. By 1900 almost half of the city’s population resided in the Basin and West End region. Twenty years later, the proportion was just about one-third.

Related Article: Black historic sites in the greater Cincinnati area.

Although every ethnic, racial, and income group participated in the enormous departure from the West End, most people who left the region were non-African Americans. By 1910, with only 6 percent of Cincinnati’s population being African American, 44 percent of the African American residents lived in the West End. Thus, the West End gradually became the primary destination for thousands of southern African American migrants to the city.

During the 1920s, the West End had become the center of Cincinnati’s African American community. The combination of a continually expanding African American population increased racial barriers to keep African Americans out of other areas of the city, and the development of very few employment opportunities outside of the West End also caused much energy and focus of the African American community to look inward.

During the 1920s, the West End had become the center of Cincinnati’s African American community. The combination of a continually expanding African American population increased racial barriers to keep African Americans out of other areas of the city, and the development of very few employment opportunities outside of the West End also caused much energy and focus of the African American community to look inward.

A lively cultural, religious, and social life emerged in the West End for African Americans. Some of the most prominent organizations were establishing important civic and civil rights institutions, such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Cincinnati’s branch of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), and the Negro Civic Welfare Association.

Related Article: African American museums to visit across the country.

These, along with many other similar organizations, were principally devoted to racial improvement, civic pride, racial uplift, and social justice for all the city’s African American residents.

By the 1930s, 70 percent of Cincinnati’s African American population lived in the West End. Most of these residents were concentrated within a 35-block radius which occurred because of several critical factors such as cheap housing, the proximity to places of employment and commerce, the location of the local railroad station at Union Terminal, and the whereabouts of numerous essential businesses, churches, and civic organizations.

Also noteworthy was the construction of the Laurel Homes and Lincoln Court Housing Projects and a 22-block area east of Linn Street, stretching from Court Street on the south to Liberty Street on the north.

Most importantly, the African American Cincinnatians would thrive wildly within these decades despite the apparent segregation. However, this era would be short-lived.

As World War II ended, numerous public officials, city planners, and business leaders began to worry about Cincinnati’s postwar development. One of the most crucial issues was the impending return, employment, and housing of approximately 50,000 servicemen to the Greater Cincinnati region.

Related Article: Public Art and History Tours for African Americans in Cincinnati

Also of much concern was the city’s continuous loss of population and industry to the suburbs. As a result, on November 22, 1948, Cincinnati’s City Council adopted the 1948 Master Plan. This Plan emphasized highway construction and community development at an elevated level.

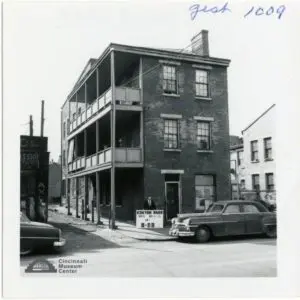

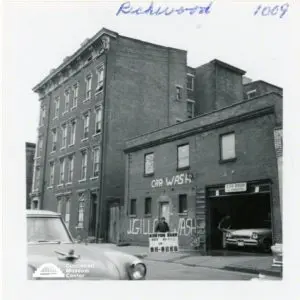

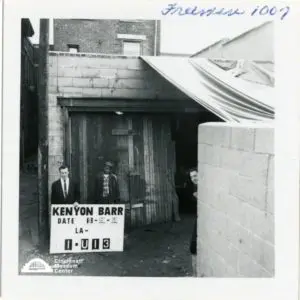

More importantly, however, after the passage of the 1944 Federal Highway Act, the West End region of the city became the focus of numerous redevelopment projects.

However, one of the unintended consequences of these city planning and community redevelopment efforts in the West End was that thousands of local African Americans were forcefully driven out of their local community and into other neighborhoods such as Avondale, Bond Hill, Mount Auburn, and Walnut Hills.

For example, the African American population in Mount Auburn increased from 2 percent in 1950 to 10 percent in 1960 to 74 percent in 1970. Also, hundreds of local African American businesses, churches, and civic organizations, such as the Ninth Street YMCA and the Cotton Club, were forced to leave the West End because of the dramatic loss in population and revenue.

Related Article: Explore Black History in Kentucky.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the remaining African American residents in the West End began to organize and try to slow down or completely stop the seemingly authoritarian notions of the Cincinnati City Council’s effort to force various plans of urban renewal and community redevelopment on the West End community.

For instance, the West End Task Force was established with members of about six city departments and individuals from the Cincinnati Metropolitan Housing Authority (CMHA), the Better Housing Authority, and the Archdiocese of Cincinnati in 1966. Also, the West End Community Council (WECC), whose origins can be traced back to the 1930s, was reignited.

Thus, during the next ten years, both organizations seem to have the power to veto all unwanted significant planning and community development projects virtually. However, by the 1980s and 1990s, reflecting the community itself, these and similar organizations in the West End gradually lost much of their political power because of several key leaders seeking and obtaining city and state political officials.

Thus, during the next ten years, both organizations seem to have the power to veto all unwanted significant planning and community development projects virtually. However, by the 1980s and 1990s, reflecting the community itself, these and similar organizations in the West End gradually lost much of their political power because of several key leaders seeking and obtaining city and state political officials.

Furthermore, sharp internal divisions and organizational fragmentation also destroyed much of the unity that had characterized such organizations in previous decades.

Cincinnati & Hamilton County Public Library’s West End Stories Project podcast captures the stories of individuals who lived in the West End during the second half of the 20th century for urbanites today who want to know more about the neighborhood’s transformation.

Bibliography

Hurley, Dan and Paul Tenkotte. Cincinnati: The Queen City – 225th Anniversary Edition San Antonio: HPHbooks, 2014.

Davis, John Emmeus. Contested Ground: Collective Action and the Urban Neighborhood. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991.

Harshaw, Sr, John W. Cincinnati’s West End Cincinnati: Create-Space, 2009.

Taylor, Jr. Henry Louis, (ed.) Race and the City: Work, Community, and Protest in Cincinnati, 1820 – 1970 Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

Taylor, Nikki M. Frontiers of Freedom: Cincinnati’s Black Community, 1802 – 1868 Athens: Ohio University Press, 2005.

About the author, Eric R. Jackson

Eric R. Jackson holds a doctorate from the University of Cincinnati. He is a professor of history and black studies in the Department of History and Geography at Northern Kentucky University, where he teaches courses in American and African American history/studies, race relations, and peace studies.

He has over 50 publications, including articles in such journals as Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, Journal of African American History, and Journal of World Peace.

[email protected]

859-572-5816

The Voice of Black Cincinnati is a media company designed to educate, recognize and create opportunities for African Americans. Want to find local news, events, job posting, scholarships, and a database of local Black-owned businesses? Visit our homepage, explore other articles, subscribe to our newsletter, like our Facebook page, join our Facebook group, and text VOBC to 513-270-3880.

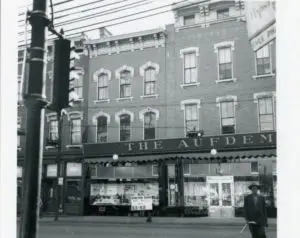

Photos provided by Eric R. Jackson, Ph.D.