OTR Cincinnati and the recurring history of racial tensions and economic divide.

The migration and settlement of African Americans into the community in Cincinnati, Ohio was known as Over-The-Rhine (OTR) started about a century after the neighborhood was created.

However, the establishment of OTR Cincinnati began several decades after the city was founded in 1788 when Israel Ludlow, Matthias Denman, and Robert Patterson purchased almost one thousand acres of land from John Cleves Symmes. Although the town was founded in 1788, Cincinnati did not become the official name of the city until two years later, in 1790.

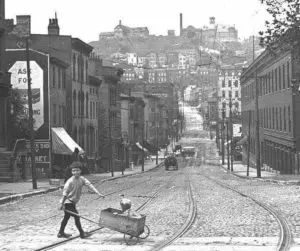

However, the city’s intense population expansion of German-born residents in Over-The-Rhine began during the early 1800s. Furthermore, it was not until the construction of several other areas during the 1870s, coupled with the establishment of an electric trolley-car system during the 1880s, the population sprawl and economic growth of the city move beyond the crowded Basin of the central city region.

In 1825 the German population of OTR Cincinnati consisted of sixty-four people; five years later, in 1830, German Cincinnatians amounted to only about 5 percent of the city’s total population. Ten years later, when the German population amounted to almost 30 percent of the city’s residents, the local government began to publish its ordinances and laws in both German and English.

Although between 1840 and 1850 the city’s German population almost doubled, the massive migration of Irish immigrants to the Queen City reduced the German residents, proportionally, to about one-fourth of the city’s total population.

Hardships during migration clash

As was the case with many other mid-nineteenth century cities, in Cincinnati, poorer people and most newly arrived migrants to the city resided and worked primarily on the outskirts of the central city, including several groups of African Americans, while wealthier and highly influential people lived in the business district and the city center.

Thus, most of the thousands of German-born residents and recent German migrants lived well beyond the Queen City’s River Basin. They primarily settled in a densely populated part of the city, which had a Germanic flavor that became known as Over-the-Rhine. This community gradually evolved into a network of streets and alleys, coupled with closely built rows of residential buildings and local shops.

Like many other immigrants at that time, and even today recently arrived German-born Cincinnatians faced a harsh array of problems and hardships during their early years in the city in their attempt to locate any full-time employment opportunities. During the mid-1800s and early 1900s, collectively, however, at least initially, many German migrants to Cincinnati possessed a great labor-force advantage, compared to other racial and ethnic groups who migrated to the city.

This labor or employment advantage was that many German immigrants were skilled and semi-skilled workers who rather easily located jobs as bakers, cooks, and tailors throughout the city. More importantly, the training abilities and mechanical skills that many German immigrants brought with them to the city also helped to establish the foundation of Cincinnati’s emerging printing and machine tool industries.

Life for African Americans during the war

When World War I erupted in August 1914, many Germany-American Cincinnatians almost immediately began to view the war as an opportunity to rekindle the unity spirit of their German heritage and ethnic community with the creation of numerous local relief organizations and social institutions rooted in their cultural traditions and traits that alarmed many local Cincinnatians.

But, on April 6, 1917, however, the day that the United States officially declared war on Germany, there were an enormous series of backlash activities and a powerful anti-German sentiment that came upon the city. This situation quickly led to the almost complete destruction of the local German community in OTR Cincinnati. Simultaneously, a small but potent group of African American Cincinnatians began to settle in Over-the-Rhine.

Related Article: Learn about the history of African Americans in Cincinnati

African Americans had migrated to and settled in several surrounding neighborhoods in the city during the previous decades with more frequency right before and during the United States entered World War I. In general, the migration of southern African Americans to northern urban centers, which started as a small stream during the 1880s, began to flow as a mighty river after 1910.

African Americans had migrated to and settled in several surrounding neighborhoods in the city during the previous decades with more frequency right before and during the United States entered World War I. In general, the migration of southern African Americans to northern urban centers, which started as a small stream during the 1880s, began to flow as a mighty river after 1910.

Eventually, Cincinnati became a favorite destination of many southern African Americans who hoped to acquire jobs in the city’s long-established semi-skilled industries such as clothing, shoe, printing, liquor, and soap. Also important to this new and intense migration pattern of African Americans to the city were the possible employment opportunities in Cincinnati’s newly established mechanical, chemical, iron, and steel industries.

Furthermore, when many southern African Americans traveled to Cincinnati, they stayed because after they arrived, they could not afford to move to another city. As a result, between 1910 and 1930 Cincinnati’s African American population reached about 28,000. By 1930, this number made up 11 percent of the city’s total population. More importantly, however, many of these residents had to find a different neighborhood to live.

Damaging Economic Affects African Americans

As the great migration of southern African Americans continued to the city, and the West End filled with newcomers who were too poor to live anywhere else, hundreds of African American Cincinnatians slowly began to move to Over-the-Rhine. However, this new intercity migration pattern did not diminish the importance of the West End, which during the 1920s had become the center of Cincinnati’s African American community. But, indeed, gradually a few hundred African American Cincinnatians began to move to Over-the-Rhine and find great living facilities.

This movement ended abruptly, however, with the coming of the Stock Market Crash and the emerging Great Depression, in many parts of the city’s economic sector, as well as the economy of the nation. The damage was felt almost immediately. A primary indicator of the destruction of the city was the extremely high unemployment rates. For example, from 1931 to 1932, among African American Cincinnatians, who at the time made up about 11 percent of the city’s population, only had one-third, full-time employment. Furthermore, about 54 percent of the local African American population was unemployed.

Related Article: Cincinnati’s ties to the Underground Railroad

Before the 1930s, however, in local housing, a small group of reformers in the city began to pressure city officials to improve its overcrowded neighborhoods, especially in the West End and in Over-The-Rhine. An important organization that led this campaign was the Better Housing League (BHL), which was founded in 1916.

The main goals of BHL were to prevent residential areas from the kind of population density and deterioration that had come to many parts of the city by using zoning to limit the areas where multi-unit housing could be built. Also important to these efforts was to deal with the high crime rate and poor health care conditions that manifested into various diseases, such as tuberculosis and cholera, which had emerged and affected many residents in both the West End and Over-The-Rhine, particularly because of the neighborhood’s unsanitary conditions.

Thus, the city passed its first zoning act on April 1, 1924. At the same time, other housing reformers initiated several campaigns to convince city leaders, businessmen, and industrialists to build better homes for their employees. Still another group of reformers focused their attention on the restructuring of the local government with the belief that there would be less corruption among local politicians and thus better enforcement of the existing and emerging housing laws. However, as previously stated, almost all of these efforts came to an immediate end with the onset of the Great Depression.

Politics over People

As the Great Depression took hold, Cincinnati’s political leaders began the process of purging its inner-city of alleged slums, including Over-The-Rhine. More specifically, in 1933, the city planning commission proposed the destruction of many neighborhoods that were adjacent to the African American-dominated West End and started to build several superblock public housing projects. The West End was further devastated by a 1948 city plan that placed the construction of Interstate 75 in the middle of the community, along with the displacement of thousands of African American residents.

However, Over-The-Rhine was spared from these deadly efforts. But, as thousands of German American residents had moved out of Over-The-Rhine, an exceptionally large population of Scots Irish Appalachians of Kentucky, West Virginia, and Tennessee began to move into the neighborhood. With the rise of this new immigrant group, growing problems emerged for many city leaders on how best to handle the new challenge of finding the correct way to assimilate these newcomers to the city.

Simultaneously, more African American Cincinnatians continued to move into Over-The-Rhine. There, they and their Appalachian neighbors found a great amount of housing, especially subsidized residents, courtesy of the new federal section 8 tax credit system for landlords. Initially, some African American businesses, churches, and social organizations emerged in Over-the-Rhine with great fanfare.

Related Article: African American political leaders in Cincinnati

However, the unintended result was an abundance of absentee landlords who scooped up substantial amounts of property very inexpensively throughout the community, some of which stayed vacant for decades. Thus, the community began to crumble, which resulted in the downward spiral of many local African American businesses and community organizations until the 1970s.

By the 1980s, Over-the-Rhine had become a hotly contested community between absentee landlords, historic preservationists, and several city officials who campaigned for urban economic development at any cost. Also, hundreds of local Over-the-Rhine residents were trapped in a world of violence, high unemployment, and poor schools. This situation was stabilized temporarily when the city passed its 1984 urban development plan that effectively researched Over-the-Rhine for low-income citizens.

However, the neighborhood did not see any significant, structural changes until about after the 2001 Cincinnati riot that occurred as a response to the shooting of an unarmed African American teenager named Timothy Thomas, by a white police officer, which was the 15th such shooting in a five-year period.

Police Relations & Gentrification

Following the riot, African American activists led an economic boycott of the city. Eventually, the ACLU and the Black United Front continued to pursue a lawsuit filed before the shooting alleging racial profiling, and the settlement led to The Cincinnati Collaborative Agreement, a plan to improve police relations with the community.

Following the riot, African American activists led an economic boycott of the city. Eventually, the ACLU and the Black United Front continued to pursue a lawsuit filed before the shooting alleging racial profiling, and the settlement led to The Cincinnati Collaborative Agreement, a plan to improve police relations with the community.

More importantly, however, for Over-The-Rhine, 3CDC, a privately financed community designing and economic development company was created to primarily obtain federal funds using a new program called the New Markets Tax Credit system, which was intended to spur investment in distressed areas.

Also, numerous major local future 500 companies, such as Proctor & Gamble and Macy, kicked in about $50 million to redevelop Over-The-Rhine for their benefit. In short, 3CDC began the process, which continues today, to buy up properties in Over-The-Rhine, some 1000 parcels at a time, and engineered a lasting Renaissance and gentrification of the community that left most local African American residents almost completely out of the redevelopment process and seemingly powerless to define the own destiny.

Related Article: Many African Americans had generational ties to the West End.

Further Readings

Davis, John Emmeus ed. Contested Ground: Collective Action and the Urban

Neighborhood Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991

Hurley, Daniel and Paul Tenkottee. Cincinnati: The Queen City’s 225th Anniversary

Edition San Antonio, Texas: HPN Books, 2014

Miller, Zane L. and Bruce Tucker. Changing Plans for America’s Inner Cities:

Cincinnati’s Over-The-Rhine and Twentieth-Century Urbanism Columbus:

The Ohio State University Press, 1988

Mitchell, Lawrence F. Over-the-Rhine: A Part of the Cincinnati Cultural Landscape

University of Cincinnati MA Thesis, 1980

Race Gap Widens in Over-The-Rhine, The Cincinnati Post 12 May 2001

Woodard, Colin. What Works: How Cincinnati Salvaged the Nation’s Most Dangerous

Neighborhood Politico 16 June 2016

About the author, Eric R. Jackson

Eric R. Jackson holds a doctorate from the University of Cincinnati. He is a professor of history and black studies in the Department of History and Geography at Northern Kentucky University, where he teaches courses in American and African American history/studies, race relations, and peace studies.

He has over 50 publications, including articles in such journals as Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, Journal of African American History, and Journal of World Peace.

[email protected]

859-572-5816

The Voice of Black Cincinnati is a media company designed to educate, recognize and create opportunities for African Americans. Want to find local news, events, job posting, scholarships and a database of local Black-owned businesses? Visit our homepage, explore other articles, subscribe to our newsletter, like our Facebook page, join our Facebook group and text VOBC to 513-270-3880.

OTR Cincinnati Photo credits: Eric R. Jackson